Introduction:

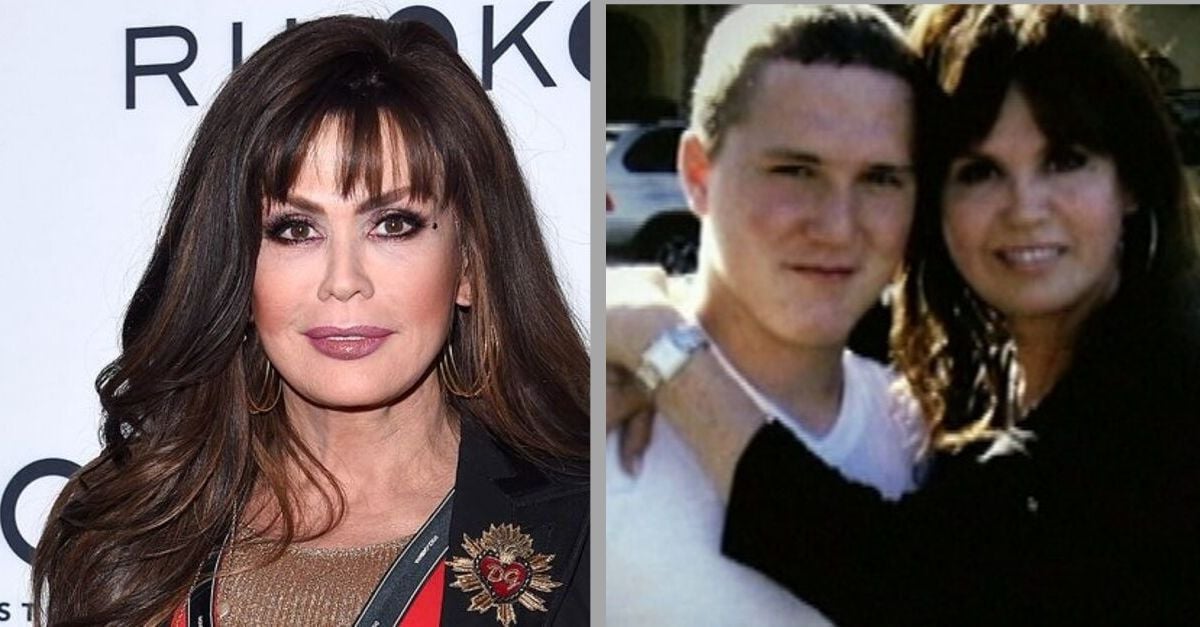

A Mother’s Unfinished Conversation: Remembering Michael

In her new book, she writes for the first time about the suicide of her son, Michael — a story she has kept partly private until now. People who knew Michael only in fragments may be surprised to learn the everyday tenderness behind his nickname, Mard. Born with a small, puckered lip, he looked to his mother like a little duck; the image stayed with her and with him his whole life. As she researched the meaning behind “mallard,” the duck’s image kept returning — graceful on the water, yet paddling furiously beneath the surface to stay afloat. To her, that image became a painful metaphor for depression: calm exterior, hidden struggle.

She speaks frankly about depression from both the parent’s and the survivor’s perspective. It’s not abstract; it’s a lived, bewildering experience. She remembers a time in her own life — driving up the California coast at age 40 — when dark thoughts made her feel that “everybody would be better off without me.” That memory, she says, gave her a rare vantage point: as an older person she could sometimes recognize that those thoughts were irrational, but an 18-year-old like Michael lacks that hard-earned perspective. That absence of perspective is one of the cruellest parts of suicide: there is no closure, no chance to correct a wrong turn.

Her family’s survival has required daily choices. She chose, for her remaining children, to keep going — to return to work, to stand as a steady presence for siblings who retreated inward, who wanted to hide from school, from friends, from sports. She credits one small habit for keeping that tether intact: she always ends conversations with her children by telling them how much she loves them. That commitment, she says, became a lifeline when everything else felt unmanageable.

One moment in the book is especially heartbreaking: a phone call that went unanswered on the night she was about to go onstage in Las Vegas. Michael called; she couldn’t pick up because she was running late. Her daughter Rachel took the call and spoke with him. He told Rachel, simply, not to marry the man she had been considering, and said, “I love you.” Later, when she reflected on what Michael might have wanted to say, she believes it would have been the same: “I love you, Mom.”

In the days after his death she experienced a vivid, peaceful dream that changed how she remembers him. In that dream there was a place between sleep and waking where, she believes, the living and the dead can almost touch. She saw Michael there, and then her own mother appeared. Her mother asked Michael if he was okay; when he nodded, she took his hand, touched his face, and said, “Come with me.” She woke gasping — but not with panic. In that moment she felt certain he was okay, that he was with her mother, and she found a fragile, reluctant peace in that image.

Her book does not attempt to provide tidy answers — there are none — but it does offer an honest portrait of a family learning to live with absence. It describes the complicated interplay between visible smiles and hidden suffering, the quiet negotiations that go on in the spaces between children and parents, and the hard work of choosing to keep living when the heart would rather give up.

If there is a message she wants readers to take from these pages, it is this: depression often hides behind ordinary faces and gentle humor; compassion and presence matter immensely; and simple, repeated affirmations of love can be a small but crucial anchor. Her story is a reminder that grief doesn’t end with a funeral. It becomes part of daily life — a thing carried forward, reshaping how we speak, love, and remember.

For anyone who has been touched by loss or who struggles with thoughts of self-harm, she urges patience and understanding — for others and for oneself. There is no single way through this, but honesty and connection can open the narrowest doors. In sharing Michael’s story, she hopes to honor his life and to reach anyone who needs to hear they are not alone.

Video: