The Grand Ole Opry might be the most famous stage in country music, but it doesn’t exactly pay the bills.

Yes, every artist who steps on that hallowed circle gets paid, but don’t go thinking it’s superstar money. The going rate is about $140 a show, straight from the AFTRA/AFM union scale. That means Garth Brooks, Dolly Parton, or a kid making their debut all get the same check. Put it this way, most of these artists make more on merch sales at the parking lot stand than they’ll ever make from the Opry. It’s pocket change, but nobody plays the Opry for the cash. They do it for the honor, the bragging rights, and because if you’re country, you’re expected to tip your hat to that stage.

So if the money is not it, what’s the real prize? Membership. Becoming an Opry member is like being knighted in Nashville. It’s invitation only, and management holds all the cards. They do not care if you’re selling out arenas every night. They want to see if you respect the roots, if you’ll keep showing up, and if you’ll carry the Opry’s torch instead of just chasing your own spotlight. It’s part accomplishment, part commitment, and a whole lot of Nashville politics.

And don’t think it’s just about being popular on the radio. The Opry has been known to pass over chart-toppers in favor of artists who show up consistently and honor the tradition. On the flip side, they’ve tossed people out before, too. Hank Williams Sr. was booted in 1952 for missing shows because of his drinking, and Jerry Lee Lewis got banned after going rogue on stage in the 1970s. The Opry might be about family and tradition, but they’ll slam the door quick if you don’t play by their rules.

Keeping your membership isn’t easy either. Members have to play at least ten shows a year to keep their slot. That might not sound like much, but when you’re a touring superstar pulling a million dollars a night, carving out time to play for $140 a pop feels less like loyalty and more like charity. Still, plenty of big names keep coming back because of what it represents. It’s the connection to the past, the chance to stand where legends stood, and the stamp of approval that says you’re part of country music’s core family.

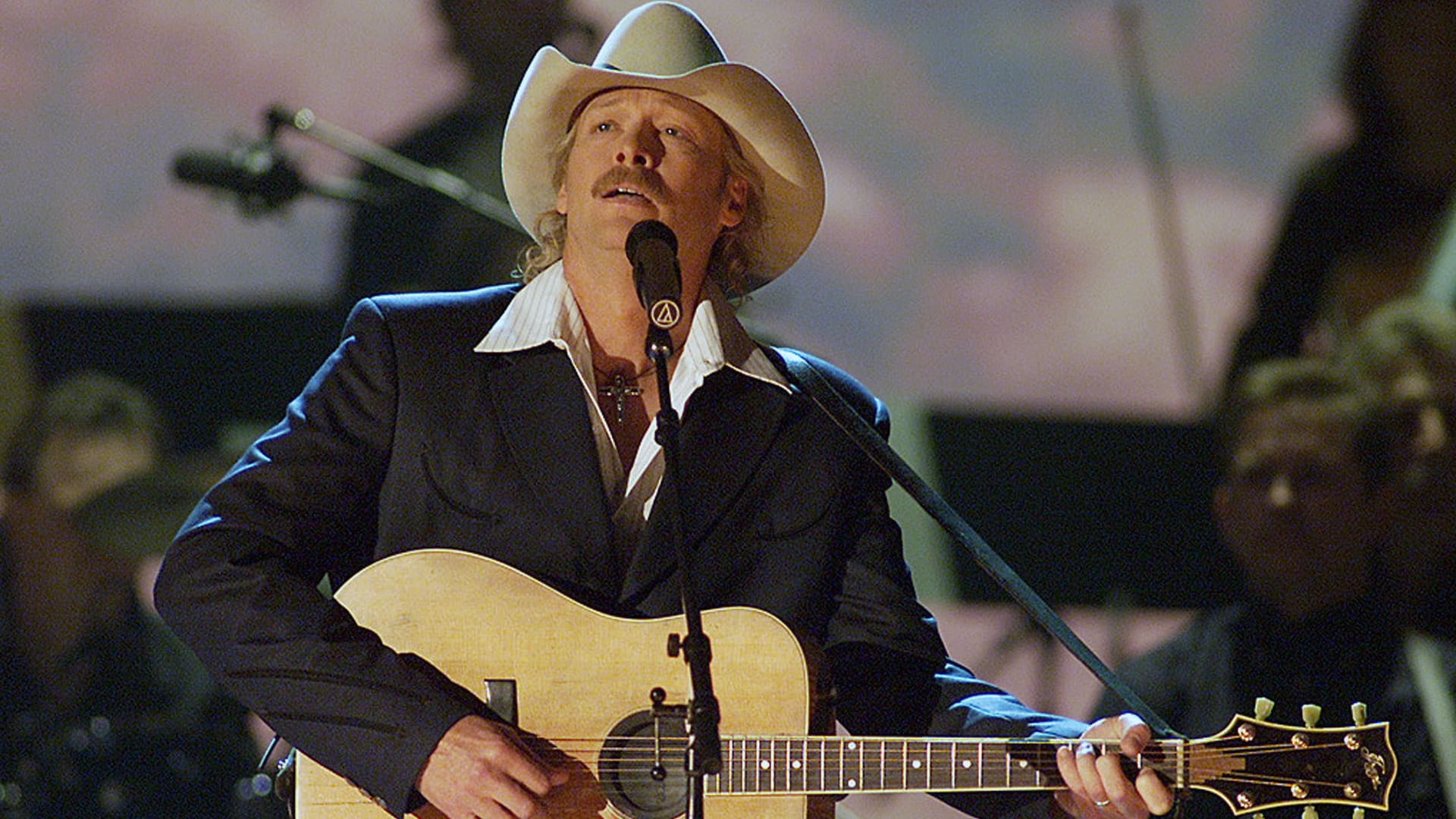

And the list of members proves that. From Dolly, Reba, and Alan Jackson to Lainey Wilson, Carrie Underwood, and Luke Combs, the Opry blends the old guard with the new blood. It’s not just singers either. Comedians like Henry Cho and even the Opry Square Dancers hold membership. It’s about keeping a balance of styles and generations, which is why you’ll hear Vince Gill pickin’ one night and a hot new radio darling the next.

The Opry has shifted its rules over the years to keep membership realistic. Back in the 1960s, you had to appear twenty or more times a year. Now, with touring schedules and big-money gigs dominating, it’s down to ten. A couple of Friday or Saturday shows can count for triple, so stars can knock out their quota in a handful of weekends if they want to. It’s a system that lets the Opry keep its star power without demanding too much from artists who could easily skip it altogether.

At the end of the day, performing at the Grand Ole Opry isn’t about money. After all, $140 barely covers gas and a late-night Waffle House stop. But it’s about something Nashville still pretends matters: legacy. Membership says you belong in the same breath as Johnny Cash, Loretta Lynn, and George Jones. It says you’re not just passing through, you’re tied to the history of country music itself.

And that’s why artists keep walking onto that stage. Not for the paycheck, but for the circle under their boots, the applause from fans who still believe, and the honor of being part of the longest-running country show on earth. The Opry isn’t a job. It’s a badge, and in Nashville, that badge means more than money ever could.